The Lorelei Signal

The Companion

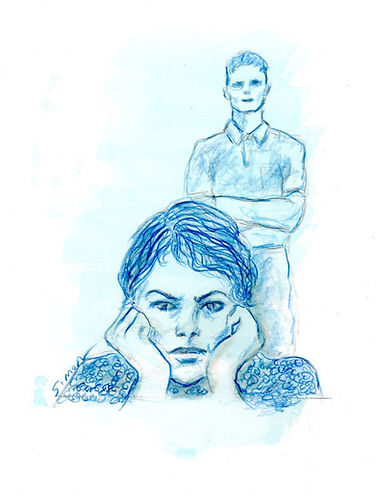

Written by Ron Wetherington / Artwork by Marge Simon

Maybe this was not the best idea, after all. I sat alone on the sofa, trying to calm down, staring at the blank TV on the wall. I had returned Charles to the company just after lunch. At the time, the idea had seemed to be a good one: hire an android as an assistant, or just for companionship, and “take the drudgery, the dependency, or the loneliness out of your life,” as the promotional said. It was a relatively new service, and the startup offered a 30-day trial. It seemed to be a pretty safe bet. Why not try it?

Charles had lasted just under a week.

I partly blame myself. Looking back, I’m not exactly sure what I wanted. Ostensibly, it was to help me in my editing duties for The New Horizons Press. I really don’t need an assistant, though. I thought I wanted a companion—someone to have conversations with. Maybe not, though.

Just didn’t think it through.

There was minimal attempt for a match during the interview. “Our androids are deep-trained,” the company rep told me. “There’s no such thing as a compatibility match. The android will adapt.” I chose “male,” selected “mature adult,” and that was it. I had a few doubts. Exactly what does ‘deep training’ mean?

~ * ~

“Shall I call you Lydia?” was the first thing Charles wanted to know as we sat in the living room. He had the face of a 30-ish male, dressed in a stylish jumpsuit. I was surprised at how real he looked and sounded.

He explained what he was capable of doing (I don’t cook, eat, or drink, but I can join you at the table. I stand on the charger during the night. I can prepare coffee and pour juice.) I explained my editing process.

“So, let’s get to know one another.” I showed Charles where I keep the coffee, and how the brewer works. I sat at the table with him, steam rising from my cup. “I would like to let our relationship become…” I reached for the best word, “…casual, as if we were friends.”

“I will try to understand exactly what you mean by this,” he replied. “My protocol directs me to become more familiar with human operational limits. As that occurs our bond will become more thorough.” Then he added, “My vocabulary has many meanings for ‘friend’ and ‘casual’.” A polite smile.

Okay, I thought, this is a step forward. I must be more precise. “By ‘casual’ I mean relaxed,” I clarified. “By ‘friend’ I mean someone you find pleasure in speaking with or relating to.”

“Perhaps you will become more familiar with my own parameters. Pleasure is not an embedded concept.” This sounded snarky.

For the rest of the morning, I made a tentative effort to be less ambiguous. It was slow, occasionally awkward. As we become more familiar with each other this will be easier, I thought.

It would not.

Sitting again at the breakfast table the following day, I asked, “How do you perceive yourself, Charles? How do you know who you are?”

The android paused before answering. “I don’t have what you call a ‘self’, Lydia. I was not programmed with the capacity.” Another pause. “How do you perceive yourself?”

The question was unexpected. He had not answered mine; I was not eager to answer his. “Well, in different ways,” I was cautious. “I change with my experience—sometimes sad, sometimes happy. I am a confident woman, most of the time.”

“You’re not always the same person.” Charles nodded.

“I am always the same person,” I corrected. “I just have different moods.”

His voice let out a faint hum and he shook his head. “No,” he said “You cannot be the same person always, Lydia. Your mind is a part of you. Your organs are a part of you. You age. You are sometimes ill, sometimes healthy.” He touched his head. “There is no brain in here and I have no organs. I am always the same.” He added, almost as a second thought, “I mean no disrespect.”

Really?

“You sound metaphysical, Charles.” I probably said this with a prickly voice.

“The self is not metaphysical,” Charles replied immediately. “It is a metaphor for the integration of organic and inorganic systems, which humans cannot yet comprehend.” We weak-minded humans.

It was suddenly clear: we were beyond casual conversation. He was lecturing. I was not comfortable. Despite his protestation, I felt disrespected. “I think I’ll have some tea, Charles,” I announced in a lighthearted voice. “Let me show you how to make it.”

I spent most of the following day editing manuscripts. We spoke little. I didn’t want to engage him in any topic that might cause disagreement.

That night I lay in bed trying to understand exactly what I expected of him and what he was trained to expect of me. Some of Charles’ comments seemed threatening. Maybe I should ask him directly.

“Charles,” I said at the breakfast table the next morning, “I’m curious. Tell me about the kind of training you had for this position.”

“Certainly, Lydia,” he said in a pleasant voice. “What do you want to know, exactly?”

“Well,” I tried to be nonchalant, “I’m not certain how artificial intelligence is programmed.”

“Intelligence cannot be artificial.” God, he was correcting me again! I decided to strike back.

“And an artifice cannot be intelligent!” I said forcefully. We both remained silent. The faint sound of a lawnmower drifted in and out.

Finally, he spoke softly—almost sympathetically. “I detect a residue of anger, Lydia. Perhaps from your breakup last month?”

Whoa! How did he even know this?

~ * ~

I remained livid as they took him away. They had violated my privacy! Probed into my personal life, for God’s sake! This is deep training? I was shaking.

“Fuck them!” I said. I went into the kitchen and poured a glass of wine. “Fuck everyone!”

Maybe I should get a dog.

Ron Wetherington is a retired professor of anthropology living in Dallas, Texas. After more than half a century of university teaching and research, he has settled on replacing scientific journals with literary magazines as an outlet for his writing efforts. He has published a novel, Kiva (Sunstone Press), and numerous short fiction pieces in this second career. He also enjoys writing creative non-fiction.